The Mind-Kitchen

A Virutal CNF Microchap

by Basil Rosa

Aloft Somewhere Beyond Comprehension

This gargle, this rumbling, this wonderment.

With each opening of my eyes comes a realization, stronger than the last, that I will forever be pumping cream into doughnuts and eclairs long before dawn, laying them out in their sheet pans, ready for the oven. Such a dream. Such a life.

My boss, faceless and nameless and sexless, says, “A whole lotta people like a sweet breakfast on the go.”

I tell myself I don’t do this dream work for money. I do it for clarity, for consciousness’ sake. I’m skilled now, and as I work, there’s a sense of the now – without past, without future – that overtakes my body and allows me to stand more upright as I labor to fashion these pillow-soft treats and take pride that I’m so fast, so accurate that the boss would rather pay me than invest in the use of a cream-dosing filling injector machine. I like knowing that in dreams I’m not a phantasmagorical being, but an asset derived from the gravity-bound heat of my father’s longing.

Pausing, I draw back my window curtains and stare at the soft morning without sun. The dream has ended.

There’s an intimation of light in the sky, and I hear the birds gathering in the trees that surround my building. Doves, pigeons, magpies, the occasional cheep-cheeps from a posse of starlings. It was the trees that sold me on taking this place, and they don’t disappoint, even in winter when they look so harsh, denuded of their foliage, like varicose veins in black against the white sky.

Waiting, I’m always waiting. What for? I cannot say. Perhaps it’s a matching audible manifestation to answer all the tension I feel stewing inside. At this moment in time, I don’t want to hear the machinations of my nervous system, its synapses firing, its connections enforced in that alchemy that floats blood into and around flesh and bone.

Where have they gone, those sweet still seas that once murmured and rippled within?

No time. Enough already of this musing. There’s work to be done. I could dawdle here all day. Perhaps this is why I work, knowing it brings focus into my days, provides a structure. I’m no good to myself when idle for too long.

*****

Ah, the traffic. As I drive, I start emptying myself of the litany of mistakes that have shamed me of late. I start revisiting all those men, who’ve been—at times—either a brother or a father figure. I love women, but it’s men I need now, figures who’ve understood the drive in me, the force that I must offer to the universe as a small thank-you and contribution. I believe life is best when it’s about me giving back rather than just taking or, as some might say, accepting.

I think of so many sometimes-driven-until-insane men, these friends of friends, these avuncular cohorts, these makers. Will I ever return their generosity? I hope so. For the time being, I must single them out and, while doing so, cleanse myself of any sequences I can recall from the nightmares I experience while asleep.

Dreams. A favorite movie by Kurosawa. I must leave dreams behind and look to what the sunrise and my work in the big mind-kitchen will bring. I feel a sense of lucidity in one recollection of a dream moment when I viewed the massive furry paws of a polar bear plodding over snow that spread textured like a lamb’s woolen coat. In that dream, I saw myself watching myself—how I stood in a straddled stance, feet planted as if my legs were the tines of a wishbone, and my upper torso like a slender joint papered in a show of breeding under control.

I have such dreams often, and I prefer, during downtime in my car, to slay them into extinction while keeping a cigarette or a toothpick between my teeth. My life is no longer an adolescent fantasy of rescuing all the betrayed children and other innocents from various gulags. No longer am I a succulent assassin bolstered by the warmth of an understood accomplice, a wingman, nearby. I’ve become dull, reliable, trustworthy, and I don’t mind. This ‘yes’ to conformity has brought freedom through a side door and a third eye, and when I walk now I fancy myself a slender glint flashing off a stone. I’m fully alive, not a soul borrowed, not ever, and I’m willing to flourish in my time and witness the stars while expecting no voices to herald my arrival.

Boy on the rise, the make, I think. Be a constellation.

*****

So much of this freedom (or better that I use the word liberation) stems from accepting that if I were to close all past chapters and bind them between the covers of a book, seal that book, and then flee, the persistence of their ghosts would continue to haunt, so etched as those ghosts are into consciousness. Why fight what time will only ladle as more of this fire, this me?

Roadside, I see iced-over embankments of snow piled like clumped pastries, like marzipan or a stollen with white frosting that dazzles, wet and brilliant, early in this day—this winter season—and when the wind blows as it always does here, even the frozen crust over those embankments dares to release a few swirling emanations. Naturally, I think of this snow as sugar, and I’ll be looking at sugar all day long, powdered and granular, but sugar is what helps me to peer in through childhood’s window, to see how I no longer cling to old razors of wanting, what I don’t deserve to have.

Let me clarify that thought. I should say that I once wanted what I didn’t understand, that I needed to earn, first, and then accept and maintain. Take relationships, for example. They start, but they don’t end, even the romantic ones with their break-ups and heartsick echoes. The process of understanding them continues on and on until applied, sometimes subconsciously, in the wisdom used to approach the next new one. Or to refine, adjust to, or alter an old one.

Everything is about relationships, isn’t it? The thrust and parry, the fencing, if I may, of what it means to cope actively and not give up on one’s self.

*****

I’m in the mind-kitchen now, and it’s noisy, and there is only the work, though I’m with my colleagues, and to be with them is to be a cog and yet to remain still. Many of them are women who speak two languages, some of them three. They have little formal education, and they like to eat. They’re big women, love their pastry, and most of them have leathery brown or molasses-black skin, and all of them have tremendously deep smiles.

So fond am I of these bosomy dream women in their hairnets (I wear one too), in their stained aprons, and how they look at me with curiosity, perhaps respect (I hope so), or perhaps blame toward me for whatever misery they’re feeling. Maybe, behind my back, they admonish me with rumors, spiced with hatred and racism. Or else love, because I’m one of them, and I don’t judge, and I take advice from them.

What I think about them doesn’t matter. We’re on our territory now. We’re like a family. We share the mind-kitchen. They don’t tell me what I can say. I don’t tell them. My silence says it all here in this landscape of mixing bowls, whisks, funnels, nozzles, ladles, and big spoons. I find the information I don’t want and all of the lore and love I need. This is what working has been teaching me all of my life:. Work never ends. It defines who I am alone, but more importantly, among strangers.

I’ve learned much in the mind-kitchen. I can read now at a basic level in Spanish, though Portuguese is still beyond me. I use Spanish when I need to make certain connections and demands, knowing my co-workers will appreciate any lack of a need for translation despite my accent. Some of the ladies find it cute and have told me so; they still giggle at me, depending on how busy we are.

*****

Everybody hates a winner. Is this true? I’m not sure. I think most people hate cheaters more and hate being a loser most of all. Don’t quote me on this, though. Just a hunch.

I will say that the more I age, the more my dead-eyed moments in front of a mirror prove how much I despise the sight of myself fading. I’m one of the oldest ones at work in the mind-kitchen, able to turn pages back to 20th-century chapters that resonate like stale, annoying ghosts.

Nobody here talks politics or religion. We never discuss the problem that is ‘existence’. We’re all too busy for such philosophical thought, but we do talk about what we see on screens, the cutting down—or the expansion—of our waistlines, an occupational hazard for sure among doughnuts. Some of the ladies talk ceaselessly about their children—the flute trills in their voices, how they envy blonde Barbie’s hair, the scent of Pokémon’s tracks in a climate-controlled wilderness. Some of the men, and we are in the minority for sure, talk about sex, though mostly about money and sports—especially sports, indeed.

Plain and simple common sense? Am I nuts? We don’t talk much about that. It appears to me to be what one lives for but never examines. It may be gone among some, but not here. Seems to me those with too much time on their hands are always decrying how lost we are to common sense in this era of taunting and flaunting and shouts and experimentation.

When I’m home away from the kitchen, I tend to get stern and studious, aiming to learn more about the presidents voted in since I came into political consciousness. The Americanized Irish smut of Reagan. The English/Texas ‘yahoo fiefdom’ of Bush and Dubya His Son. Yale, Harvard, the inside track, Obama’s drone strikes, and Clinton’s rodeo of sexual exploits on the job.

It’s all shameful to me. I can’t think of any of them as role models, and this might explain why on paper a mediocre utility infielder in professional baseball earns a guaranteed larger annual salary than the nation’s president, certainly larger than what all my kitchen colleagues and I, combined, will earn in one year. But we men don’t talk about that element of sports. Nor do we live on paper.

There are perks, of course. I get to bring home stale doughnuts, but I don’t eat them; I donate my share each week to a local food bank. This helps me fuel the delusions I live with regarding how charitable I am, how professional baseball players donate some of their excessive shares, as well. Panem et circenses. Droll stuff.

I remember that for about a month in late September of 2001, I mistrusted and took a hard look at everything I saw and all that I’d been taught to believe in. Then I went back to work. Now, I believe nothing. The payments on accrued interest alone for each of the creditors I owe money to will keep me pumping cream into doughnuts in this kitchen for up to fifty hours a week until I’m a corpse. There are no longer any quiet Sundays for me, no evenings by the fire. I rise early and get home late. Like a beast, I rut along into the soil to maintain the mortgaged sprint lane I’ve fashioned for myself. I had choices, and I made them. I could have signed on and climbed various mountains, and I did have options; I could have, but I didn’t. I picked my numbers and slid my chips across the table.

That’s liberty for you.

Gentian

It’s a day

when I believe everything important happens far, far away from where I stand. Two of my brothers, Mark and Steven, and I are shoveling our driveway yet again. We breathe, we work with such vigor. When I pause, I look up to the sky and see it washed metallic and bright and empty of clouds, and I think of it as the boldest, most memorable sky I’ve ever seen. I can also see and smell the ripples of heat radiating from the roof of our iced-up house with its eaves toothed with icicles, and I remember that Mother is in the kitchen baking two loaves of her date-nut bread—one for us boys and one to sell at an annual church fundraiser. Later in our socks and pajamas, we’ll sup greedily on canned tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwiches, and then we’ll each devour a wedge of cake covered in cream cheese. Father will come home after dark to find his driveway clear, and we’ll go to bed early to sleep in contentment and exhaustion.

It’s a night

when what returns before sleep is a memory of an Easter when it snowed a while and later, after our family meal in my brother Joe’s house in Sutton, sunshine came on, and the sky was that unique, cloudless presence again. But at that time in my life, it seemed chintzy somehow, not natural, and less than what I remembered it as. It drove me to realize there is no single moment when we happen.

I began

at age ten to run each morning, whipping through the woods on my way to school and imagining myself an Algonquin brave. The birds began to talk to me. I talked back, but I didn’t always listen. On rainy days after school, I lay on my stomach on the floor and read, until sleepy, from a new Highlights or a Boy’s Life each month, or dog and wilderness survival stories, or a Hardy Boys novel. On sunny days, having some marbles, an arrowhead, and a jackknife meant everything. Some of my marbles were as clear as that sky, and these I never traded but kept separately in a little tin that once held shoe polish.

I leaned

at age eleven into his long silences, buffed, waxed, and shining with admiration. Every fall I raked his lawn at least twice. He never paid me, nor did I expect it, but he’d give me a stamp now and then or wheat pennies, the rarer ones minted in San Francisco and Denver. We boys, my brothers and a bunch of kids in the neighborhood, would walk down the street with him and feel safe because he was so big and older, and we feared and idolized him. He did all the talking, mostly about PT boats and how fierce and honorable the Japanese fighters were in a place he called the Pacific Theatre and how they deserved our respect. How respect meant everything in this world.

Then one day

he just wasn’t around and my father had to explain that he’d left us for a better place and wouldn’t be coming back and that I should bring a plate of Mom’s home-baked cookies to his wife and just sit with her for a while. That plate was made of glass that equaled the color and clarity of those skies I remembered.

I brought it to her, and we sat and ate cookies and drank hot chocolate and she washed the plate afterwards and I took it back to my mother. I didn’t tell anyone that I didn’t understand any of this. Nor did I know that such a color could have its own name.

Chase Scenes

The world chases money, so you chase money too.

—Arnold Wesker

Winter memories were waiting to be found. Markets were closed. Anything hot had been claimed. So, roundly arid, I learned how to drift and how to re-varnish each surface I’d worn. I heard and rejected as vital the lie that success is conquest and gain that my charter should equal Ginsberg’s Howl, and that I should use only a Number 2 pencil whenever I tried to sketch a dog’s laughter.

The mind, a trunk full of impressions, and I couldn’t write to empty it. I had ideas, such fiery obsessions, lists of whom to enshrine and defend. Green mountains, milky ponds, the kingdoms to come where I’d mingle, seeking places to stand fresh, hopeful, looting, and locked in.

I took advice whenever possible toward the pursuit of means and began to realize the ultra-rich, like the ultra-poor. are invisible. I read Paul Fussell’s piquant Class, where he lays it all out succinctly. It’s “new” rich who show off their lucre. They want others to know they once had much to prove.

I began to not labor, but to be merely an embodiment of size, cunning, and arrogance, seeking to show more than indifference or piety. I grew less popular the more I avoided either/or and all-or-nothing-at-all approaches. Half measures made the most sense and kept me whole when flagging. Spending time in Russia, learning the language, seeking to fit in, I began to appreciate survival as a means of doing and thinking by half. Not all. Never all. The rumors of my failures were only as exaggerated as I allowed them to be in the stand-off between what’s seen and doubted, versus what’s rumored and manipulated and spun as truth.

Finding a saint or two to emulate, favoring Augustine and Francis of Assisi for starters, I began to decorate myself for each stranger in every hive where I could meet them, absorbing their eloquence, erudition, and applications of efficiency and belief.

I’m still living a one-lifetime ride up and down, dipping after dosing on scales that weigh the reaches between goodness, sloth and licentious. Not the whole of anything, but just enough of any spontaneous eruption to keep me humble as a form of imperfection seeking refinement.

I have my deaths, my chase scenes, bouts of paranoia and longing as I lament what I believe to be engineered forms of demise. I have my memories of a day’s work done. These bring peace and kinship with the giving soil. Long ago, I moved to city life, and I miss farm work: the fresh air; the ride home from my days working in North Carolina tobacco-hanging barns, riding in the back of an F-1 Ford pick-up along winding roads with blankets of kudzu spilling down from the steeps and across the macadam. Off in the distance, a wavy line of sapphire blue, and beyond that another horizon, a greener blue that was hazier and formed a seam of low hills to mark earth from sky, and I’d get lost in those seams. Before I knew it, I was back at my boss’s house with the others in his family, including his son and brother, and all the day’s work and the chase scenes were over, and it was time to feast and be grateful in our weary bones.

Recently, I rode through those hills west of Asheville after being away for thirty years, and I kept thinking the quiet’s gone, the solemnity, that there are too many cars, storage units, and dollar stores. Too many dry cleaners, payday lenders, and empty storefronts in the town. I didn’t even recognize the boss’s old farm since it had been chopped up into lots, each of the barns and coops—remodeled, leveled, or else used for other purposes—owned by different families and concerns. I thought it a detachment from the land thoroughly executed.

I watched a car pull into the driveway of the boss’s house. It was a car that looked like all the other cars, a two-door sedan, gray, made in Asia no doubt, and assembled by robots. Not a trusty Ford F-1 pick-up anywhere in sight. Not one truck on what had once been a farm of over 1,000 acres tucked away as if – at least in my mind – a sanctuary off the beaten path.

A woman got out, and I saw she was alone and looked pale and lonely and tired and was maybe thinking of bar-coded food and a screen experience and some form of narcotic and a weekend to come without companions and not needing to drive once more into the growing cities that kept moving closer and closer. I thought back to times before banking was mostly direct deposit and online to those evenings when my weekly check would arrive. The eagle flies on Friday, Saturday I goes out to play. I carried coins then for phones, vending machines, for a street beggar. I can’t remember when I last jingled coins in my pocket.

Happiness, I suspect, cannot be taken away because it isn’t given. I viewed it then as I do now, as earned, lost, rediscovered. I remember, paycheck in hand as I clocked out, how I’d smile out of nervousness at the misery I saw in my co-worker’s faces. Was I just as miserable? Some of them glared at me as if I were a lunatic. Others sneered while others cheered. A mixed bag, as always, when it came to co-workers. I often refused their invitations to go drink at a favored gin mill until I was blind. Perhaps some of them were right. Perhaps I was a lunatic. Perhaps I still am and perhaps there are no angels and no stormy Mondays and no freedoms and none of this is a beautiful dream.

*****

I used to work on a packing line with William. We called him The Waltz King. Such moves he had. Such a singing voice. Some guys get by in a factory because they don’t let anything kill their spirit. William believed nothing existed until it was seen by more than one person.

Enrico worked with us too, and he was always laughing at William, because Enrico believed all that existed passed through each of us, one at a time, as a unique form subject to interpretation. Enrico’s spirit lives on inside of me, too.

Lastly, there was fat Jacques with his ginger beard, who I swear walked out of one of Shakespeare’s popular comedies, and one day at lunch told us that his reason for living was his search for an eighth age to add to his famous “seven ages” speech in As You Like It. This proved I’d been correct in assuming Jacques wasn’t real, that someone had dreamed him up, even though he was one of the fastest and most efficient workers on our line.

You can learn a lot about human nature and resilience and your own shortcomings by working a line for a while.

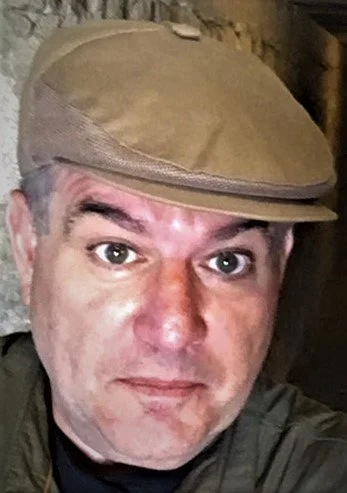

BIO: Basil Rosa writes from England. He also writes as John Michael Flynn, and his latest books are the short story collection, Vintage Vinyl Playlist, and the essay collection, How The Quiet Breathes. Find him at jmfbr1@blogspot.com, where he writes about other artists, authors and places he's been.