The Last Days of School

by Mary Ann McGuigan

Our students are lined up in uneven rows, staring stiff and bright-eyed into space, like they’ve just heard shocking news but can’t stop smiling. Sometimes I wonder if they’re imagining another life, a place where they’d have new outfits and clean shelves to sit on, instead of being stuffed into carboard boxes under the bed at night.

Mindy keeps listing to one side, so my sister Irene twists her legs none too gently to keep her from tipping over. She used to be our favorite because she looks like Marilyn Monroe, but ever since Marilyn divorced Joe DiMaggio, we don’t like her that much anymore. Joanie can’t sit straight either, but me and Irene both have a soft spot for her. Her body is all squishy, but her plastic head has a crack in it now because Daddy threw her against the wall last week. I was running for cover and left her behind on the floor, so she was underfoot when he staggered into the living room. Barbara hasn’t done her homework. That’s nothing new. She’s dressed like the queen at a coronation, thinks she’s above it all. I hide her shoes sometimes just to put her in her place. Betty is in the back row. That’s where we keep her. She’s the tall, blonde bridal doll with the too-perfect face. We decided early on she was the mean one, catty, hurtful. I doubt she’ll ever change. My favorite doll is Kelly, an Irish peasant girl, with a long apron and wild red hair. I make up stories about girls who find out they’re adopted, girls whose real families are rich or even royalty, and Irene helps me write them down. Then I read them to Kelly so she won’t feel so bad about being poor.

We always play school on Mama’s full-size bed, and the size of the class increases by two every Christmas because me and Irene each get a doll under the tree, identical except for their dresses. But Irene’s are always dark-haired, like she is. Mine are either blondes or redheads. Sometimes we have parties with them and pretend they drink too much. They end up fighting, with lots of hair-pulling and dresses torn. We never let the new ones drink.

Irene is almost always the teacher. She’s nine, only two years older than me, but Mama puts her in charge of me and my little brother when no one else is home. Irene can be bossy, but she watches out for us, lets us know when to stay clear of Daddy. But I already know that because when he’s been drinking a lot there’s a smell that covers him like a nun’s long veil, like a warning. Sometimes, if he hasn’t had too much, he comes home in a jolly mood and gets us all out of bed, ready to make smoke rings or sing Perry Como songs from the Hit Parade or get Mama laughing with stories about his great-aunt Fionnuala, who told him he’d wind up a thief because his mother clipped his toenails when he was a baby rather than bite them off. Early on Sundays, sometimes, he drags us out of bed to dance, has us mimic his clumsy jigs, tells us we can skip Mass. He lets us swing from his outstretched arms, lets us break the rules when Mama isn’t around.

He’s tall, six foot one, tall enough to reach up and palm the ceilings in our basement apartment, has arms long enough to hold three of us at once, tight enough to keep us still. His eyes are filmy gray, like if you put Vaseline on stones from the shoreline. He jokes about losing his hair, but I don’t think he really cares. I’ve never seen him use a comb. He puts his fingers through it as if it’s in his way, especially when he listens to the Yankees on the radio and they mess up a double play or walk two men in a row.

Irene puts our little blackboard down and steps into the living room, finds the record she likes to dance to, “Dance of the Little Swans.” She loves it because she can twirl all over the room, even leap off the couch. She wants to be a dancer. She’s good. She can’t wait to go back to her dancing school. Mama enrolled her six months ago, because everyone can see how good she is, but she had to drop out. We don’t have the money. Irene says she loved it there. The instructor taught them the French names for the steps done at the barre. That’s a pole hung on its side, not the one Daddy goes to all the time.

The door to the apartment creaks open. It’s our brother Sean. He’s home from the Daitch Dairy, where he works after school. He mumbles hello, heads for the kitchen, and Irene puts the record away, comes back into the bedroom. “I don’t want to play school anymore,” she says.

“How come?”

“I have to start getting dinner ready.”

“Okay,” I say, but I worry that Irene is getting bored with playing school. Sometimes she doesn’t want to play dolls at all. She says she’s not a kid anymore, not really. I get why she thinks that. She has to do so many chores now, especially dinner, because our older sisters are married. Nora got married almost two years ago, when she was sixteen. Kathleen turned sixteen last January and now she’s married too, so they’re both doing their own dinners. Sean is fourteen, old enough to help. So is Danny, he’s thirteen, but boys in our family never have to help out in the kitchen, so it’s all left to Irene. She never complains.

I shove Mindy off the bed. “It’s not fair,” I say.

“Mama can’t do it,” Irene says. “She has to work. You know that.”

“Yeah, cause Daddy drinks all his money.”

“Stop.”

I pick up Joanie, use her voice to say what I’m thinking. “I don’t love Daddy anymore.”

“You can’t say that. It’s a sin.”

“I can’t help it. He hurts people.” Mama was bleeding again last week, from her nose this time.

“I know he does.” She says it so Sean can’t hear, like she might get in trouble for saying it out loud. I’ve heard Sean asking Kathleen why Mama doesn’t leave him, or at least call the police when he threatens her. Kathleen says there’s nothing we can do. And that’s what Irene tells me now. “There’s nothing we can do.”

“It’s not like that with all dads,” Sean says. He’s standing at the door, his hand on the doorknob, ready to go out again. “It doesn’t have to be this way.” He slams the door behind him. Sean seems angry a lot lately, says he’s joining the Navy as soon as he can.

I follow Irene into the kitchen. She raises her leg, rests her foot on the kitchen table, her toes pointed, repeats the exercises she learned at the school.

I love school too, real school. I finally started first grade this year at St. Thomas Aquinas. It’s on Daly Avenue, about half a mile from our apartment building on Mapes. I walk there in the mornings with Danny and Irene. We always walk up Tremont Avenue and sometimes, when we get to Daly, Danny wants to go left, to the Bronx Zoo. Irene won’t do it. “We’ll get in trouble,” she says. “Are you crazy?”

“I ain’t crazy,” he says. But he kinda is, because he’s done it more than once. He hates school.

Not me. I love it. My teacher, Mrs. Richardson, says I’m a fast learner. I love books. Irene has been teaching me letters for a long time on our toy blackboard. We talk about the story books from school, the beautiful pictures, the beautiful places people live. Our dolls come from places like that. But Irene doesn’t want to play with our dolls that much anymore, especially since she left dancing school. Mama promised her she’d teach her the steps she was learning. Mama’s a good dancer, says she danced with her brother in Parish shows when she was a girl. But by the time she gets home from work, she’s too tired. So she hardly ever dances with Irene. She still sings sometimes though. When she was in her twenties, she sang in jazz clubs in the Village. But they were dark and smoky places and people drank too much, I guess, because when Grandma found out about it, she got so angry she forbade Mama from doing it anymore, called her a loose woman. Mama won’t tell me what that is, but she insists she was no such thing. Her brother Johnny tried to stick up for her, but nobody gets to tell Grandma she’s wrong.

It wasn’t fair to keep Mama from singing, like keeping Irene from dancing. Me and Irene are always fair to our students. There are rules in our classroom. No shouting at each other, no calling names like slut or bitch. But I can’t make life fair for Irene and I’m worried she’s going to leave, the way Nora and Kathleen did. But if she does, I know she’ll find a way to learn to dance the way they do on television and she’ll be happy. But there would be only one doll under the Christmas tree. And who would I have to play with? Who would even notice me here? I’d have no one to help me write my stories down. I’d have to recite them to Kelly from memory. Someday maybe I’ll have a place I can go, even if it’s only make-believe. Then I’ll be happy too. But I’ll take Kelly with me. She wouldn’t want to be left here.

*Originally published in Bluestem (Spring/Summer 2024)

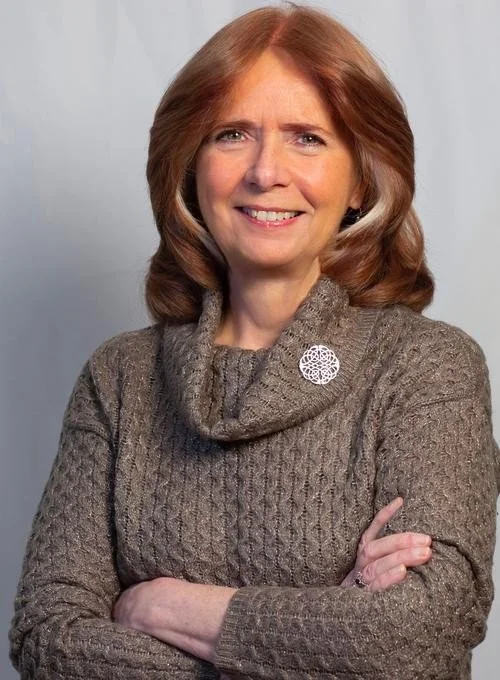

BIO: Mary Ann McGuigan’s creative nonfiction has appeared in SmokeLong Quarterly, Brevity, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. The Sun, Massachusetts Review, North American Review, and many other journals have published her fiction. Her collection Pieces includes stories named for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net; her new story collection, That Very Place, reaches bookstores in September 2025. The Junior Library Guild and the New York Public Library rank Mary Ann’s novels as best books for teens; Where You Belong was a finalist for the National Book Award. She loves visitors: www.maryannmcguigan.com.