Six Poems

by Jack Mackey

Lilies, Lilacs, Lavender and Still My Mother Dances in Luberon

The house smells amazingly purple, a single vase of violet

lilies from our garden, planted by you, you cut and arranged.

Who’d’ve guessed how much such scents quicken to my frontal

lobe, spaces where my mother lies waiting in the crevices––

memories of her blinking, like blitzy neon, typically supplanted

by fresher recollections, like a kid’s broken leg, a day in divorce court,

a guardrail I’d like to forget forever. Today behind

these old eyes are lilacs fixed in the front of my childhood home,

blooms sparse from my negligent watering, except one she planted around

the side, near the dripping outdoor faucet. As if it knew its special role,

that bush bloomed a wand of blue stars. On balmy days, she’d finish

folding wind-dried washing, take clippings and place them in glass

milk bottles, set them around the house. Last summer, a bicycle

through the south of France, the whole mountainside ablaze in blue

and even the lavender-infused food and the sachet (now in my closet)

never smelled as alive as her lilacs that wander through my head,

carefree over those fields planted deeply, deeply in the faults,

the sweet cracks where my mother never looked so beautiful.

Don Bachardy Turns 90

On the beach at eighteen where

Isherwood found him, already

a chest like chiseled granite. The dirty,

dirty old writer took him home and he never left, slept

in the old guy’s bed, later sketched him naked in a wheelchair,

in the bath as his craggy body caved in on itself, and stayed

with him. Stayed in the house another fifty years,

drawing the gathering of LA stars, racking up

the accolades, aging alone. Love over-

lapped like the pyramids

and mammoths––

out-living one

another.

Yesterday you wouldn’t let me

help you lift the chaise lounge onto the patio,

a spring ritual for ten years now, saying No so loud I worried

the neighbors would hear us (me crying I’m not feeble yet)

and they might believe I am. I was pledging a frat when you

were putting a tooth under a pillow. I catch you

watching me when I get up from the couch,

as I chop peppers for the salad,

stick a bloody finger

under the faucet.

I yell to you

write your novel,

get good at

something––

for later.

Searching for Godliness in the Mission

My sister and I scurry about this house

we borrowed so our still-unrooted baby brother

has a place to die. Assorted people I’ve never

met before have shown up for a week,

to hug him, sip herbal tea, tell stories.

Then last night he slipped away in sleep

as if he tried to spare us all. He was the only one

ready. Two strangers come in a van, tattoos

every visible inch, & whisper we’re sorry,

call us family as in, Family, is it OK

to go out the double doors? and I am struck

how the collective noun sounds now.

Dying has disordered this old Victorian.

My sister’s on her knees in a bathroom,

and I take charge of laundry.

I think how his forehead felt

on my lips when I kissed him

yesterday. And of our mother,

who needed one of us to stay, made him

pancakes until he was 28,

watched the door for years after he left.

I pull the sheets from his bed, a tattered

gray shroud, worn spots,

the odd body mark. I remove my clean shirt,

roll up dank bedding in my arms,

dump a healthy cup of Clorox into the machine.

Now we get ready to go, listen

for the dryer to buzz, like how you know

a screen door will always slam,

and brace for it. I remake the bed

& call out to my sister, “The stains are

gone.”

As we lock up the house, it starts to

sink in, starts to drizzle.

Our taxi approaches, its wipers smearing

the windshield––a distant bell

from the church, a few streets over,

the Angelus rings through the fog.

Onions

Today I’m trying to watch

a YouTube interview with a poet

I admire, but my eyes keep wandering

across the laptop screen

to the other shows. Before I made coq au vin

again last Sunday, I reviewed

Ina’s demonstration. She mispronounces

coq, says, “cock.” I guess she

knows her audience. Ina shares a secret

of frozen pearl onions, no one needs

to peel, no one needs to know.

It’s my favorite thing you make, you say.

The leftovers are still

in the fridge, but I have a need

even now––is there a better way

to make it, am I missing some

ingredient? Would you love it more?

Now Martha’s video lures me away

from the poet, so I click Pause on him

and fire up her demo.

She doubles-down on lardon, splashes vinegar

on her onions before chopping.

I make a note then go back and finish

the interview with the poet,

his discussion of his divorce, the lyrics

leading up, what he wants now.

Later this afternoon I’ll try to

write about this, I’ll use onions

in a metaphor, a tied handkerchief

shielding my eyes.

Father-Son Tournament

On the next tee he says, Let’s work

on your swing a little. His arms wrap

around me from the back, he presses

into me a little, places

a foot & taps my sneakers

into place. He is trying,

I can feel it, to connect, fix

something he fears maybe he broke.

Wheezing in my ear,

exhaling tobacco, he lowers

his hands on my hands, aligns

his arms with mine. It’s awkward

to be this close, for both of us.

He needs something but I have

no idea what it is.

Heads together, we face down,

our arms in parallel. He is silent

as I raise the club, my guided stroke

lifts back, lifts up, stops for an instant

in the air above, then whoosh!

His strength, his twisting forces

my stiffened torso into one smooth spin

and together we launch the ball,

watch it float over a sand trap &

slice into the morning mist, drop on the green.

For years I thought he wanted to change

me, but today I realize

I was wrong––as I drop my son at soccer

practice––and he gives me a hug

spontaneously, without my asking.

Stealing Jones Beach

I am eight. The trunk is lined with a threadbare

baby blanket, satin trim fraying, us four kids

squished in the back seat where we await our mother.

Last to arrive she commands the neighbors’

attention. Casual but carefully done up in her A-line

and her clip-on earrings––thin mother-of-pearl

discs outlined in rhinestones––she reaches across

the painted steel dashboard & adjusts the plastic

Madonna with quiet superstition. South along

the Meadowbrook Parkway, a nippy Sunday in April,

an air of expectation blows through open windows

extending the scent of my father’s tobacco, we glide

towards the beach and coast along sail-shaped dunes

that hide the breakers we can hear pounding. A mound

of white sand stands up suddenly, immaculate as a newborn

cloud , and my father abruptly pulls off the road.

I watch as he presses the parking brake,

turns to my mother and pats the back of her hand.

Her expression droops around the edges.

With motor still running he walks around

and pops the trunk, calls to me to join him,

hands me a shovel and whispers, Quick.

I copy his rhythm as we stab

our shovels into the sand and empty them

into the trunk, ignoring my mother’s protests––

Walter, it’s illegal––trying to load as much

as we can before a cop arrives. All the way

home they argue over my father’s

decision to “save a few measly bucks” on

a backyard sandbox for my sisters. It’s obvious

to me they are angry at more than this pilfering,

but I know better than to ask.

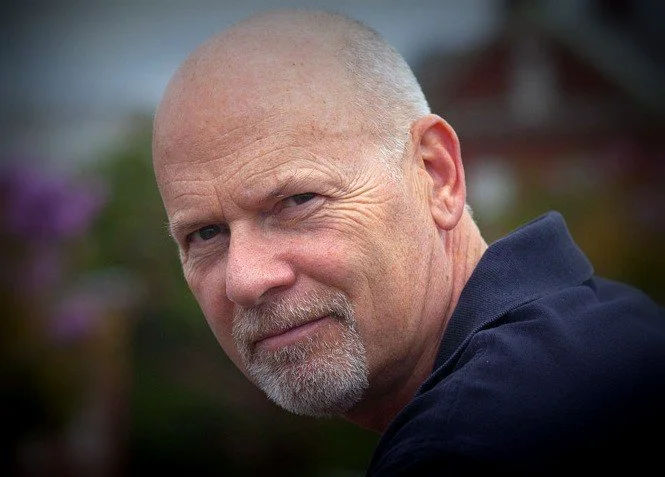

BIO: Jack Mackey grew up in New York and earned his M.A. in English from the University of Maryland. His first book of poems Up, Out & Over (Kelsay Books, 2024) won first prize from the Delaware Press Association. Jack was awarded a fellowship in poetry by the Delaware Division of the Arts and was selected for the Disquiet International literary program in Lisbon, Portugal. Individual poems have appeared in Gargoyle, Third Wednesday, Broadkill Review, Impostor, Anti-Heroine Chic, Mobius, and other literary publications. Jack lives in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware and Wilton Manors, Florida.