The Russian Brontosaurus-Cow as Seen with Faceted Vision: On Vladimir Sorokin’s The Sugar Kremlin

by Eric Vanderwall

It is Christmas 2027 in Russia. The Red Troubles, the White Troubles, the Gray Troubles—all these dark times recede into an ever more distant past. It is now the Renaissance of Rus’. The Russian people are safe in the mighty hands and under the watchful eyes of Vasily Nikolaevich, the Sovereign of all Rus’, whose will is carried out by those “enemies of internal destruction,” the Sovereign’s secret police, “the heroic oprichniks,” who tear internal enemies of the people “into little bits.” To protect his people from the hordes of external enemies, the Sovereign has ordered the construction of the Great Wall of Russia, which grows by the day through the diligent, purely voluntary work of convicts and schoolchildren. On Christmas, the “Bright Day of the Birth of Christ,” a crowd of children gathers on Moscow’s Red Square, in the shadow of the Kremlin (which the Sovereign’s father, Nikolai Platonovich, so wisely had whitewashed during his reign), to witness the beautiful, pure face of the Sovereign, projected on the clouds. After he wishes them a merry Christmas, multitudes of red balloons bearing parcels descend, and each child receives a special gift from the Sovereign: a Sugar Kremlin, miniature replica of the Kremlin made entirely of sugar.

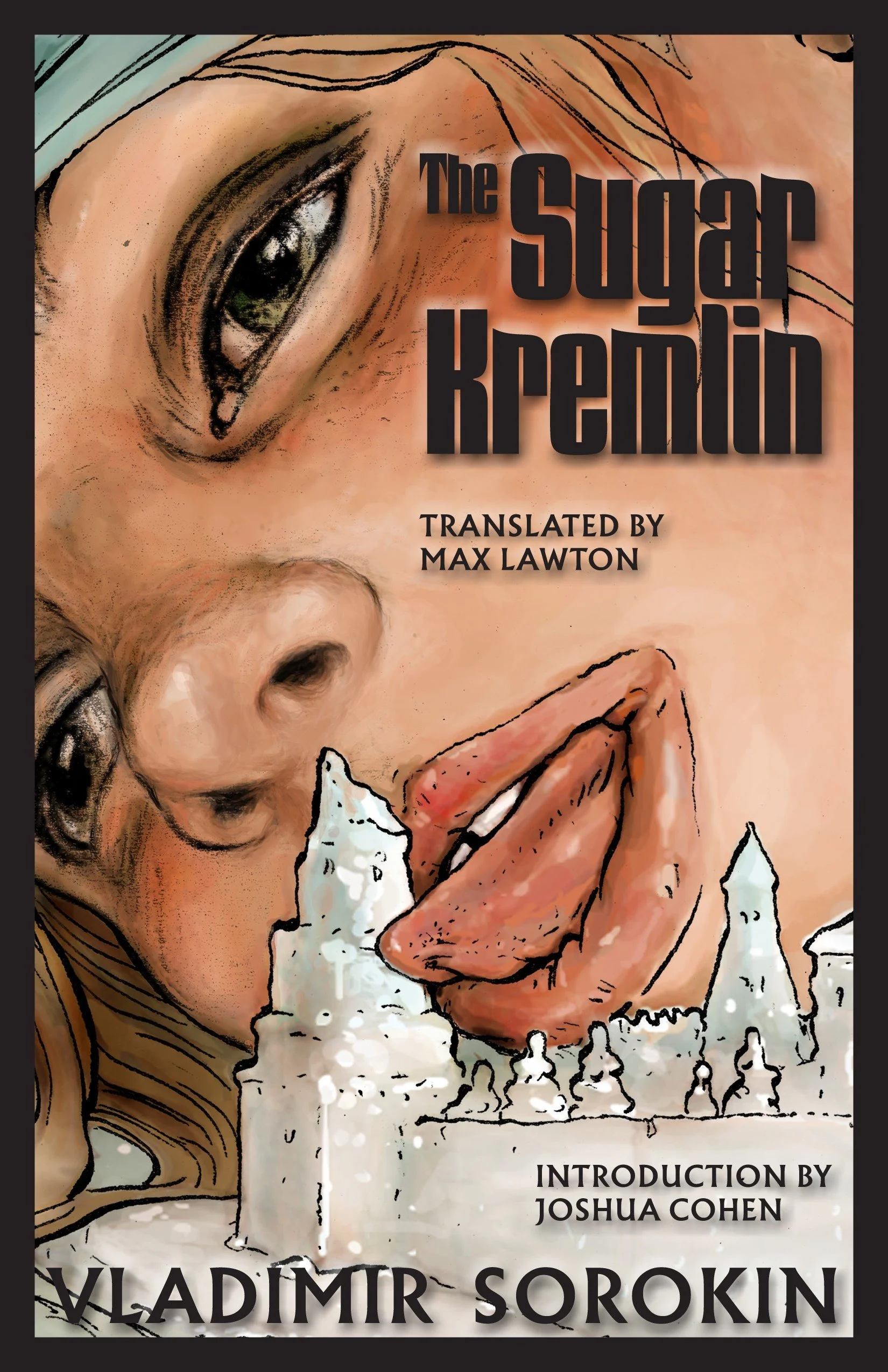

Such is the Russia the reader encounters in The Sugar Kremlin, Vladimir Sorokin’s collection of linked stories, first published in Russian in 2008 and now translated into English by Max Lawton and published by Dalkey Archive Press. This volume marks something just past the midway point in the joint Dalkey-NYRB effort to publish Lawton’s translations of Sorokin’s previously untranslated work (with The Norm expected from NYRB sometime next year). The Sugar Kremlin is nominally a sequel to Sorokin’s 2006 novel Day of the Oprichnik (which, naturally enough, follows the activities of an oprichnik—a member of the secret police—over the course of one very busy day), but one need not have read that book to understand this one (insofar as Sorokin is understood rather than experienced).

Like Day of the Oprichnik—and other works such as Telluria and The Blizzard, and Blue Lard to some extent—the Russia of The Sugar Kremlin is a near-future, techno-medieval state, in a period after cataclysms alluded to but never specified, and well along in the latter stages of societal failure. (Unlike the comparable settings in those books, though, a few stray references to the Putin era, Marc Ribot, and Gogol Bordello indicate this world is connected to our own.) People speak in a mix of contemporary slang and archaicisms, such as yon, thee and thou, thankee, verily, and must needs, sprinkled with borrowed Chinese phrases. People on the street (many of whom are waiting in long queues of the kind common in the Soviet period) might stop traffic because of the gnomic pronouncements of the blessèd Amonya, a kind of institutionally recognized holy fool (or maybe merely a madman taken for a saint), and hoist him high above their heads that he may better point out the “trouble,” like a scene out of Russia’s premodern history, yet the same Amonya walks a blue-eyed, electric dog. Other characters might buy goods with a moving graphic, a “living label” or a “living image,” on the packaging; they might wear “big, shaggy ‘chameleon’ sneakers made out of viviparous plastic,” a “red robe made of viviparous terrycloth,” or “self-generating furs”; they might play a 4D computer game called “Guojie” (according to the footnotes, a Chinese word meaning “state border”), which “became popular in New Russia after the infamous events of August, 2027”; an especially well-off character (and only the oprichniks, who carry out the Sovereign’s Word and Deed, and the nobility are so well-off) might drive a “Merstallion the color of steamy blood”; and almost every character, regardless of age or social station, has a Smartypants for making audio-video calls, playing computer games, and looking up important facts (such as how many more bricks are needed to complete the Great Wall—"62, 876, 543 bricks”). And as these examples illustrate, some of these technologies (such as robot dogs and robot servants) are easily visualized, while for others (such as the Smartypants or an eleven-year-old girl’s semi-conscious tooth-cleaner and “layered comb”) it can be hard to tell the shape and appearance, which seems to be a deliberate choice to make this fictional world somewhat opaque, somewhat hazy, such that the reader is never quite certain how the world works (an apt feeling when depicting life under authoritarianism), as well as to direct the reader’s attention away from the (fictive) science of these gadgets and toward how these technologies function socially and politically.

The Sugar Kremlins the Sovereign distributes (or that are distributed by unseen forces as an enormous projection of his face gazes down) bind together the collection’s fifteen stories (which take place from Christmas 2027 until late the following autumn) and, more abstractly, bind together all of New Russia. Itinerant beggars, blind and disfigured, ration out pieces of a Sugar Kremlin as part of their meager evening meal. A screenwriter breaks off crosses from the Cathedral of the Archangel and drops them in her whiskey. Two farmers break up a Kutafya Tower and have it with their tea. Pieces of the Sugar Kremlins also make their way into more sinister settings. A Captain of the State Security sucks on the last of a Sugar Kremlin’s seven two-headed eagles after interrogating and torturing a suspected enemy of the state. A brigadier overseeing forced convict labor on the Wall separating Russia from China, after monitoring mandated selective flogging for failure to maintain the Sovereign’s schedule for his Wall, allows one of his charges a bite from a Spasskaya Tower. And, in the kind of grotesque humor prevalent in much of Sorokin’s work, prostitutes in a brothel grind up an Ivan the Great Bell Tower and sprinkle it on the rather large penis of the large oprichnik (who weighs in at seven poods) who is their regular (and of course beloved) customer. And at the factory where the Sugar Kremlins are made, in a room storing rejected Sugar Kremlins, a supervisor bends his teenage (and mentally handicapped) subordinate over one such wreck and has his way with her while she licks one of the towers. (A portion of the illustration depicting this unsettling scene features as the book’s front cover.) Of the many ways to interpret the Sugar Kremlin (to spell out too many would do too much to impose comprehensibility on a book for which disorientation is an important part of the experience), one is as a physical manifestation of the Sovereign’s reach. He never appears in the stories himself (being something like the unapproachable void at the center of this fictional world), but his power touches on every aspect of life in this Russia. No one escapes the Sovereign.

The Sugar Kremlin presents another fine entry in the catalogue of Sorokin’s works available in English. Although The Sugar Kremlin is a sequel in a loose sense, it is not a bad entry point for readers new to Sorokin, and Joshua Cohen’s interview with the author (included as the introduction with the title “The Guts of the Russian Brontosaurus-Cow”) is especially illuminating. No other Sorokin translation to date has included such an interview, which, true to Sorokin’s artistry, explains his methods and conception of Russian history but leaves to the reader the endeavor of interpretation. Max Lawton as translator is, for better and worse, the only currently active English translator for Sorokin (Sally Laird and Jamey Gambrell, Sorokin’s first English translators, having died in 2010 and 2020, respectively). Lawton knows Sorokin personally (regularly corresponding with and visiting the author, whom he refers to rather familiarly as Vladimir), which surely helps ensure that as much of Sorokin’s intention comes through as possible. In many respects, Lawton makes good (or, in the contentious area of translation, at least defensible) choices in opting for an English version that approximates the effects of the Russian original rather than a strict adherence to literal translation (which, Lawton reasonably argues in interviews and in remarks in other volumes, can miss the point of Sorokin’s games with language). Lawton does, however, have trouble with prepositions (in English), namely the irksome tic of employing the grammatically offensive “off of” where the simpler and less aurally abrasive “off” is correct, as well as a tendency to change between past and present tenses multiple times in a story. (Such issues are not apparent in the Laird and Gambrell translations, suggesting translator shortcomings rather than authorial choice.) Nonetheless, The Sugar Kremlin is a rewarding read, a worthwhile addition to a personal collection of Sorokin, and another fine example of the author’s style of recreating (and not, as he emphasizes, describing) the world through a kind of mixing of styles and perspectives in a technique he calls “faceted vision, like what insects have.”

BIO: Eric is a writer, editor, and musician in Arizona. His work has previously appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, memoryhouse, World Literature Today, On the Seawall, and elsewhere. Please visit www.ericvanderwall.com/publications to learn more.