Shades

by Chris Negri

It is good to meet you after so long in this place alone. I feel a sort of instant affinity for you. The absence of alternatives is sufficient to explain that.

Your lack of eyes may make it a little bit difficult for us to establish a deeper connection, though. I’ve always had a thing for eyes, for eye contact, for sensing feeling, interpreting meaning there. The windows to the soul and all that. I believe it. We’ll have to connect via a different route. “The long way round,” as it were.

It has been I don’t know how long since I saw a face.

Yours, although hideous, will do admirably.

And, in any case, if I squint, as I am doing now, I can almost fill those jagged, red ringed cavities dripping with gore with something that isn’t horrific. There, I’ve painted them ice gray like my grandmother’s, and you look cool and tall and harsh. There, my father’s warm hazel, and you’re soft and kind and flaccid. There, you’re him, Alexis, the green of him, the pull of him, my husband, the person who put me here.

I won’t bother you with the details. Suffice it to say it involved another man, my alcoholism, a nightly tallboy of rum and coke, and a very sophisticated, subtle poison purchased on the dark web and delivered into my bloodstream late in the evening of Halloween 2022. And what ensued was a soft drop into sleep and a regular dream for a part of the dying followed by waking here, sitting in this shabby, dented tin desk chair.

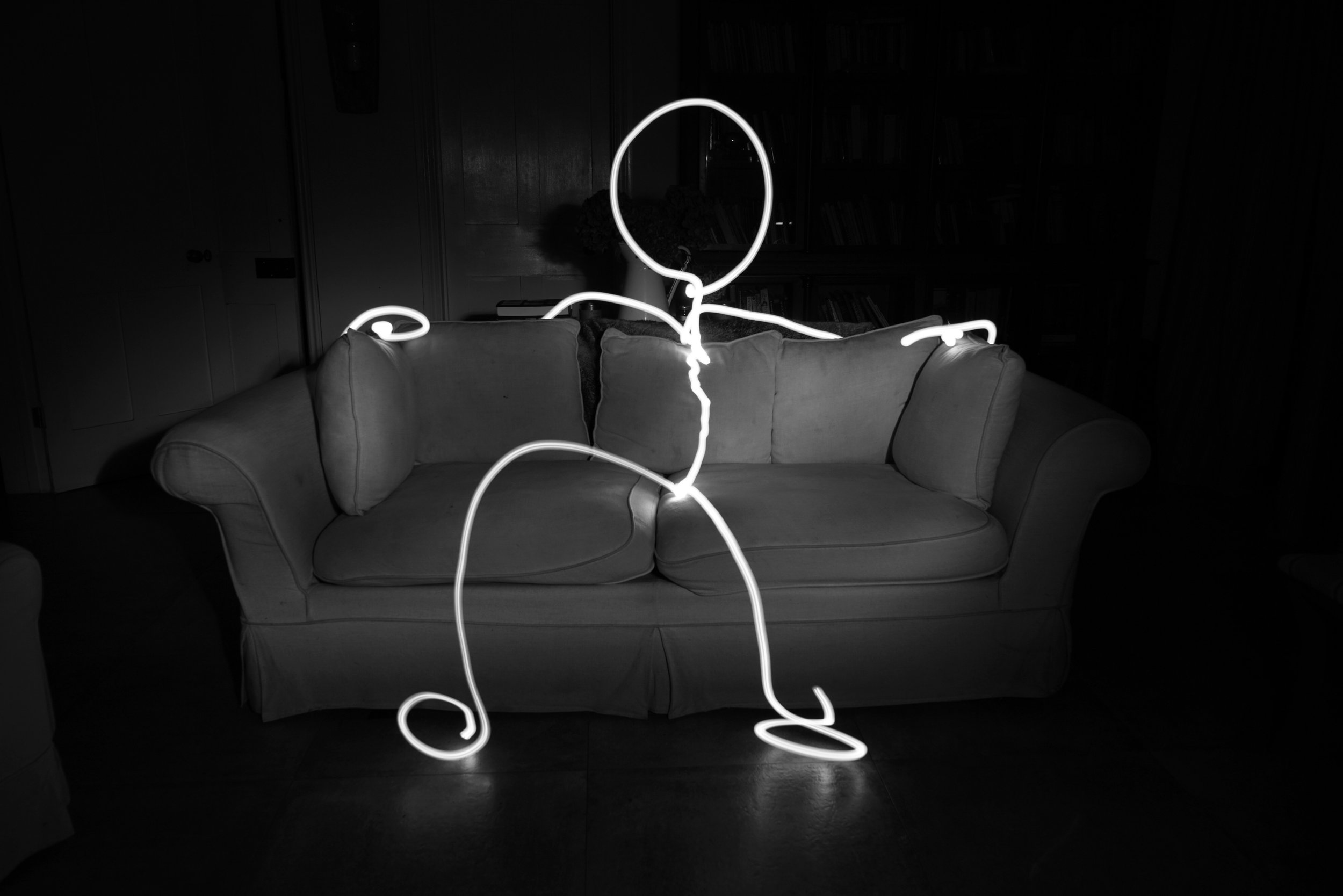

As far as what here, now, and you actually are, I really haven’t the faintest idea. We, I think, are maybe what people once called shades, something faint, a sort of outline of what we used to be. We are vaguer than the angels.

And time moves linearly sometimes and then in little flashes, out of order, absurdly slow and absurdly fast and with multiple renditions of events. I have seen, with my own eyes, at least three histories of the 20th century: the one that I remember, one in World War I never happens, and one in which everything ends on October 27, 1962, and thereafter the earth is barren and then fetid and then stunningly beautiful again by the millennium. I see my birth and death and different versions of me that are still alive in different countries. I see what my non-existent son will do with his life, his death in 2154 at the edge of the Sea of Tranquility.

It's bullshit, I think. It is what I want to see, a swirl of dreams. If I focus, and sometimes I am able, I can see the reality of Alexis and his new husband and their house in Los Feliz that they purchased with the money from my life insurance. I can see myself dead and decaying in the ground in the Forest Lawn in Glendale. I can see my parents choking on their grief, falling away from each other, sinking into old age and dementia and sad, lonely, banal deaths in the sanitized shabbiness of Verdugo Hills Hospital.

But then I look up from that and I see the two of us in this interior office no bigger than a utility closet and you looking as (frankly) startling as you do, completely naked and with your conical hat and the no eyes and the swollen Vienna sausage fingers with the fingernails missing. Or, at least, the suggestion of those things.

Tell me, do you feel?

Ah, so it’s no tongue as well, then?

I’m assuming, too, that using those fingers to write would be impossible, even if I could obtain a pen and notebook for you. And I have no idea where I might do that, or even if we can hold and use things of that nature.

Anyway, I sometimes feel that I feel things. It was that way a bit ago, watching Alexis and Robbie as they shopped for groceries, walked the dog, fucked sloppily.

Envy and resentment and a desire to see them know pain. At night, the brief glimpses of it, I was standing near their bed, watching them coiled in each other’s arms, and I was seeing and feeling my fingernails digging into Robbie’s lungs and squeezing his balls until they were flat and grainy. Sweetbreads. They looked like I was crushing some chicken livers with a spatula.

A few blinks later, though, I was standing at their parallel graves, watching their names turn illegible and the stone crack and then turn to dust.

Nowadays, I wish them both well. They’re just over there on the Panasonic, suspended in midair, and they play most of the time unless it’s a blue time. You’d have realized that by now, if you had eyes.

That’s quite the nice body there, though. Really great, juicy thighs and a beautiful round ass with just the right dusting of black hair on the skin. Couldn’t help but notice your nipples are pierced. Couldn’t help but notice now, as my eyes descend, how thick and veiny that cock is.

It’s just the suggestion of a big dick, though. I can see it diminishing even now, see the veins receding into the skin, see the head retracting back into the foreskin like a frightened woodlands creature. And now, look, it’s as fine and dainty as a furtive hummingbird.

I don’t have genitals anymore, I think.

No, I don’t mind if you masturbate.

Strange, how you communicated that question without speaking, given your lack of a tongue.

The sound of friction and spit. I remember one of my college boyfriends, a gross but beautiful boy. He once made a bunch of pasta and poured it and some mayo into a bowl and came up next to me as I was asleep in his parents’ bed and he punched and clawed and fingered the contents of the bowl, making squish squish squish noises while he moaned cartoonishly, until I woke up from it and winced at him. We had sex right then, of course. He was such a hot little pig. No manners whatsoever. But now, in retrospect, I think it’s fine, the sound of friction and spit, friction and cum, friction and lube. Does nothing for me, but I think it’s fine.

The TV sometimes shows them fucking, Alexis and Robbie. The other day, they were in their early 60s or something and Alexis was eating Robbie’s saggy, old ass, and I could see him imagining me in my late 20s, imagining my butt, which was quite something back then. By then, it would’ve been 30 something years later.

And then he switched to thinking about Doug, the dad with the nice calves across the street. And then, I saw all their corpses in the ground and watched Alexis’ face cave in over the rosy expanse of the next doomed century.

Oh, my Lord, I see you’ve cum a little bit. Good for you. That’s quite a large amount, pooling there in that crater in your belly. Oh, but when did that void in your flesh open up?

Anyhow, I have the sense that we are not actually confined by this room, seeing as we are not meat, but spirit. Look, over there, a staircase is leading up a cliff face. I once walked up that one, or another one that looked like it and ended up at the Roseville Outlets, where I bought myself a nice Fossil watch and a pair of black and white marbled Crocs which I see appear to still be on my feet at this moment. And then I kept walking, and I was in the middle of one of the camps of the Donner Party, watching someone gently carve a piece of gray flesh off the wrinkled surface of an emaciated woman’s belly.

My mind free-associated myself to the Farmer John slaughterhouse in South LA that you smell on winter mornings in Huntington Park, where I grew up. That sweet and spicy smell of pigs being killed. I never actually smelled it until I went away to college and then came back. And then the stink of death was separate and heavy, rather than so familiar as to be unnoticeable.

Oh, the screaming in there. I’ve been in there now, many times. I’ve watched them working on the pigs. I’ve listened, over and over again, to the screaming. The frequency of it, the height and sharpness of it, like the world’s longest, thinnest knife, skimming the surface of your back. Such pain at such heights, drawn out, pooling in those huge circular eyes. And the eyes of a pig look so much like the eyes of a human. Their lashes are fine and platinum blonde. I see what they do with those eyes when they’ve taken the bulk of what they need from the animal. They throw them in the great massive grinders to make sausage, and the white orbs explode and make the meat slick and juicy.

Ah, yet more cum. A prodigious, Bellagio fountain of it. And with such a distinctive milky pink color, like Pepto Bismol with the little red knots of—what is that?—actual roses?

There is a road, I think, on the outskirts of this, that leads up from wherever we are, and down as well. But I don’t think it’s really identical to that, to what I thought it was in the beginning, what we were raised with: heaven and hell.

I don’t know. A while ago… years, maybe?... I must’ve been walking in that direction for some time, because I was there, at a sort of Nautilus shell of a staircase, something very grand and Baroque, a sort of marble helix, twisting down and up in a way that sort of called into question whether what we’re standing on right now is really solid. It was sort of corkscrewing through this like a sharp pencil puncturing a piece of paper. And I stood there for some time and started staggering around and struggling for balance like I was on the ocean, and I watched people walking up and down and running up and down and being carried up and down in what looked like rickshaws and litters.

Some of the people had proper faces that you could make out, most of them with that frightening look of being prematurely withered that you see in the faces of the relatively young in very poor countries, like when you see someone in a warzone in a documentary and they’re 28 but look 50. Some others had wiped out faces, like their features had bled a bit in the rain. I remember looking in the eyes of a child and they were just streaks of blue and the child’s mouth was a solid dot of fire engine red, a perfect “O,” like the mouths of cartoon carolers on Christmas cards.

And then I saw those unmistakable eyes of his, with that unmistakable green. Like a sort of Faberge egg green. A green you see surrounded by furs and amber. Ringed with those lashes.

He looked sort of finished. There were parts of him, his legs, his arms, that looked fully formed. And his lips. And his hair.

He looked like he was in his late 30s, a little gray at the temples, a bit of gravity showing on his cheeks, but not much.

That great big barrel chest of his was bare and covered with hair, and I could almost smell him from where I stood. His body, the smell of it that I’d loved so much. The soap he used, cedar wood and smoke, some ridiculous, self-consciously masculine thing.

And those eyes were there, smeared a bit, like someone had drawn them in and then smudged them up with their thumbs. He was coming down from the floor above, totally naked. I could see he had been crying. There were streaks of green coming down, dripping onto his collarbones.

I could see that he was freshly dead in the shock that was playing on his face, in the trembling in his limbs, in the fact that his skin still had a brownness to it rather than the gray tinge that settles into everyone here with time, including you and me.

He turned as he descended and looked at me, and I could see his mouth form words, and I could see him speak rapidly, violently, desperately, but there was no sound whatsoever. He kept moving, and I could see what I had not noticed before, that the staircase was moving like one of those flat escalators at the airport, compelling everyone on it downward or upward against their will. Drawn on by the machine, he disappeared out of sight two seconds later.

It is a wonder that I ever hated or loved him.

Ah, but the smell of that is so lovely, those flowers that are growing out of the massive hole that has swallowed up your torso. Star anise and vanilla. Some fig, maybe. Plums. Pine needles.

We got married in December, you know, and we put those things in the garlands. Alexis said he’d loved Christmas, that it was when he felt most loved. Currants. Dates. Juniper. Purple hellebores. Fresh pomegranates split in half to show off their shiny innards. It’s all there, beautifully arranged, spindling upward from the puddles of semen that you’ve left on the floor.

And now the rest of you falls away, your head and your shoulders, your pierced nipples and what used to be your prodigious manhood and what is now a spray of white stars of Bethlehem.

My Lord Enki, oh, I should have recognized you. I should have seen, at your shoulders, the pure and clean rivers coming down and filling this room with sweet water and the way this dank, shabbily carpeted utility closet is opening up to reveal a broad red land that is blossoming with golden fields of barley and ripe pomegranates and figs and citrus trees and artichokes and eggplants and pistachio and almond trees. How, from your disintegrating shoulders come rivers and canals brimming with abundance, fat, silver carps and mackerels, freshwater eels that will turn sweet with syrup, salty anchovies and sardines. How, from your exploded phallus, come the fat little round partridges and ducks and pheasants and cranes and peacocks and peahens, and herds of ibexes and small deer with their beautiful, little, feminine faces and jackals and laughing doves and Bactrian camels with their funny, middle aged looking bodies, and Rüppel’s foxes with their bright, blood red eyes.

I am tired. I am ready to die, really. I am ready to diffuse, to flow out, like you, into the land. I am ready to cease my chattering, to fall silent. Every memory, every piece of pain and joy. All knowledge. Every love. My grandmother’s parchment paper hands and her pink housedresses that smelled of vanilla and her squat little house with the olive-green carpet that always smelled like star anise. Our wedding day, the ridiculous hope of it. I want it to all go away now.

Ah, there it is, the world is turning black at last. I can feel my eyes becoming jelly-like and pouring out, spilling down over my lips. Mmm. The sound is going now, a little at a time, a sort of soft ring settling. The space that was my mouth is full and dry and vacant.

Ah. Yes, black, falling like a veil over me.

It is warm.

It is cold.

It is neither.

BIO: Chris Negri lives in Los Angeles. His short story collection, Care: Stories, was published by Inlandia Institute, a small press in his native Riverside, California, in 2020. His work has been published in Entropy, The Rumpus, Maudlin House, and other publications.