Yellowtail Blues

by Lance Mason

He'd read somewhere that Hemingway had invented some of his war correspondence, that those dispatches were too similar to some of his fiction to be true. The reporting would, therefore, have been contrived, the malefactor incriminated by his own hand. Yet were they lies or just hyperbole? In addition, did anyone care? Had they read less well because they hadn't been thoroughbred fact? Someone famous said that journalism is simply man's first opinion of history.

Besides, what right did anyone have to expect the plain truth? Papa was, after all, a fisherman.

Today, for our sins, we have computers that duplicate, then surpass, man's grandest calculations. Still, for all their power, machines can neither paint the thinker's creative dream nor match a fisherman’s vivid fantasy of how it should have been.

So, it had been in that elongated instant this morning when, his fly-reel wailing its strident song, Michael Lessing's line had sliced across the broken waves, the Cinemascope of his brain snapping into HD 3-D. In that broad second, across the silver screen of his mind, he strode to the dais in pomp and glory. The darling of a festive writers’ banquet, and cheered on by his admirers, he accepted the grand prize for his piece about fly-fishing on the Sea of Cortez. His byline gracing the great sporting reviews, literary agents stuffed his hand with calling cards, and Heidi Klum was trying to get him on the phone.

The flickering scene had ended when the butt of his rod fell dead in his hand, the fish tearing away like a runaway train.

After that, hours passed. The towering Baja sun bounced its lethal heat off everything in creation, and even the fish were lethargic. As a distraction, Lessing studied the pain on the side of his face, the vivid pain of a thousand pinpricks. The day before, he'd gone out without sunscreen, and now he was burned. Worse than the broiled skin, though, more wounding, was his sense of failure, his mordant frustration over the morning's defeat.

Lessing thought about these things as the boatman's panga motored east toward Isla Carmen. From a mother-of-pearl sky above the island's peaks, the sun spilled its white-gold track across the water. Squinting to his right, through the metallic glare, Lessing studied the cliffs jutting above Carmen's ragged shoreline. Furrowed, crosshatched, their craggy flanks were frosted white with primeval plumes of pelican shit.

He looked to his left, away from the harsh glint, at Joaquín. The boatman's face, bearded and weathered, looked impassive but riven by dreams. His eyes, red-gray and liquid, like bloodshot oysters, scanned the ocean in front for a sign, as if vision alone could lead him to the fish. You'd imagine Joaquín was looking for fish, but he spoke so little, and the sea's surface revealed so little, that it seemed all a mystery.

"I'm such a goddamned fool, Joaquín."

"Jurel very strong. Very smart." He was talking about the yellowtail.

"Yeah. Yeah, I know. But I had him. He took the frigging fly. Hell, he ran with it. I had plenty of strain on him. I thought he was hooked."

"Not so many fish today."

"Yeah, gracias, Joaquín." He regretted his sarcasm. "Sorry—yeah, it's thin fishing, all right. Any ideas? Just cruise around?"

"Punta Lobos."

"Near those divers from yesterday, by the split rock?"

"Si, Miguel, y cerca canal estrecho. Vamanos. Muchas sardinas allá." The big ones would be chasing baitfish there.

"Vale, Joaquín. Vamos."

The panguero let his mouth twitch once, then eased the throttle down and worked the wheel to port. Carmen's bays and cliffs slid away to starboard and the panga rode the chop with a gentle throb.

Lessing thought about his chances. It was still February, prime yellowtail season, but the ocean had stayed cold, spoiling the spawning run and the fish counts, making his sense of despair all the greater. When there are a lot of fish to be had, losing one is not such a trial, but when the fish are scarce, the spirit not on the water, the fish you lose may be the only one you'll touch all day, all trip. When it's a fish like this morning's, then, the images can haunt you.

Visions of failure were the things Michael Lessing had come to Loreto to escape, the confrontation between his dreams and the obstacles to those ambitions. Fishing never rid him of the risks of falling down; it just gave him some freedom from thinking about it. Dropping this fish had freshened the worry.

His flight from Los Angeles had touched down in Loreto in the afternoon two days before. Riding into town in Geronimo's old dunger of a taxi, they'd rattled and rumbled along, mariachi tunes cascading from the radio and roadside saguaros saluting the passing cars. Near town, Lessing had seen a huge billboard, parallel to the road, visible to all the traffic. From it, a redheaded woman, outdated in her style—clothes, hairdo, domesticity—looked out at him over her shoulder. A hair-coloring’s slogan angled across her twisting torso in heavy, white script: ¡Cambié sus expectativas! Change your expectations! The sign's plywood backing was beetle-drilled, the paint of the ad peeling, giving the impression that the product for sale was extinct.

Lessing had been tiger-fishing in Zambia the year before. As then, he'd come down to Mexico prepared for the challenge. He'd studied his quarry in the guidebooks and knew from the get-go that yellowtail on the fly was going to be an iffy proposition. Big ones run to forty pounds. They run deep, they run fast, and they run hard for the rocks if you horse them. Taking an outsized yellowtail off the bottom with a fly rod was a fairy tale told by a few, but Lessing steered clear of that fantasy. He'd come after firecrackers, five- to ten-pound surface-feeding dynamos that schooled at the northern and southern tips of Islas Carmen and Coronado, and sometimes in the channel between.

At his local tackle shop, when Lessing had brought up saltwater fly-fishing, an old man rummaging through the bins of gear had mentioned Loreto. They'd made a date to meet for lunch. There the salty veteran had talked freely, one thing leading to another, as they do with fishermen.

"Sometimes months, years go by for a fly angler between takes. A long winter off the water, a new job, wife and kids, bad health." Lessing learned from the old man how a universe of changes and delays, of heartbreak and joy, can write new beginnings and old endings to the chapters of your life. "Another year goes by and you think your tackle is getting old. But it's your casting hand that's getting old. You count the seasons you have left on your fingers and toes, and then just your fingers. That's when you hate the wind that keeps you ashore or the work that keeps you home. You just hate the days you miss." Lessing saw the metronome of life counting away the hours, the months, until one day you realize that the fishing dreams that remain for you are numbered. "A big one may get off now and then, sure," said his friend, "but at least you're fishing."

Yesterday, his first on the water, Lessing had been skunked on yellowtail, but he'd boated three barracuda and an early sierra mackerel that he'd had for dinner. Even the grilled sierra, though—white, cake-like, majestic on the tongue—had been scant compensation for the lack of yellowtail.

So, this morning they'd gotten away before dawn, heading north. Joaquín had explored off the southern tip of Coronado, then spotted some birds working up the island's west side. They'd chased them clockwise as the birds moved a little north, then east. So, Joaquín piloted around the next point, straight into the rising sun, and, before they could adjust to the light, the boat had hit a churning maelstrom of fish, birds, and ocean. Billowing hordes of sardines flew past in their own patches of spray, with seabirds and game fish diving, slashing, leaping into the shimmering schools of feed. Common terns and black-backed gulls had rained into the water like feathered arrows. War parties of yellowtail pillaged the swells, bursting through and savaging the whirling mobs of baitfish. It was an angler's vision of Heaven.

As Joaquín throttled down, Lessing had jumped to the gunwale with his rod, whipping out line. He'd swung the rod and raised a cast, searching the water for a streak of green—two or three, even better. Then it came—no firecracker, but an artillery shell, barreling across from starboard, nailing a sardine off the port bow, and then braking, veering, as it prowled past him toward the stern. Its body looked as thick as Lessing's waist, its tailfin as wide as his chest. Lessing fired a cast that led the fish by six feet, an arm's length to its left. His timing had been perfect and so had his aim. The emerald monster broke for the splash in a cutting swerve and struck.

Later, he could remember the moment he lost it. The yellowtail had hit his fly like the wild predator it is, like a puma takes a hare. It had hammered the fly and, after the first thumping jolt, Lessing had raised the rod swiftly and let the big fish run. His rod was up, bent parabolic, and he palmed the spool, the reel making a ferocious whine. He thought he'd held an even strain. He'd thought the fish was hooked.

The green beast had dived through a deep turn to the left, and Lessing was just tightening for a surer hook-set—or had he tightened?—when the pressure fell away and the rod went limp. The fish was running at him! He'd stripped line madly, felt a tug—or had he?—and raised the rod again. Nothing. He'd stripped line again, then again. Then he'd stopped.

He'd stood holding the dead rod, the birds gone, the water flat once more. His line lay on the water like an empty vein, a single, curling thread, running to nothing. Reeling in, muttering to the boatman, he'd dwelt on his mistake, watched the blank horizon, and felt the failure burrow down into his guts.

The lessons, the methods, were not new to Lessing. When a big sea-fish hits, you must strike it right and strike it hard. Right might mean the moment it hits or after it turns and runs. You have to know—know the fish, sense its rhythm, feel its heart. A fish with the heart of a lion takes your fly and challenges you to a fight. You let it run, and then you strike—hard. But some fish have the heart of a wolf, and you must strike them instantly, before their fear rejects your fly. All fish of a type, Lessing knew, share the same heart. Permet are like rabbits, wahoo like cheetah, and tuna like Cape buffalo, dumb and relentless and hellishly strong. A marlin is like a leopard—you must use the cleverest possible ruse to draw it in, you must be quick and precise to fool it, and you must be very smart and very strong to defeat it—and you must strike it on the run.

Lessing had struck the yellowtail as if he'd been trout-fishing—tighten and lift. He rarely struck a trout hard. Okay, sometimes—down in New Zealand, on the big Tongariro rainbows. Mostly, though, he'd just tighten on the line and lift the rod, keeping an even strain. No, he’d made a mistake with this yellowtail. You can't play jurel like that.

Fishing's rarely easy. After the weeks of planning and hope, after the beer-bar fantasies, you find the school of fish and you fool one. You bring it to the fly. It swoops through in a lightning attack and is on the hook before you can think.

This morning, off Coronado, the hit had come with a vicious shock that was in Lessing's hands and arms before his brain knew a fish was there. There was no mouthing of the fly, no touch-and-go, but a fearless take by a big, hungry animal. Before the adrenaline had even lit up his blood and muscles, Michael's hands were moving, working, playing the line and the rod. Yet he'd struck the fish from bare excitement instead of craft and purpose, a going-through-the-motions strike. Then it was gone, all over far too soon.

What pained him was that his intent, his instincts, had been weak. He should have driven the hook past the barb, harpoon-like, into the fish's jaw, when the fight would have then been his to win or lose, rollicking thrusts surging through his arms, his rod kicking under the pounding, shimmying runs. The fish would have sounded madly for the rocks to break him off, his line carving Cubist designs through the ocean's ripples. He would have kept an even strain. He would have pumped and reeled and turned the fish's head as the perfectly ballistic body torqued and flew through the sea.

It didn't happen, though, and he felt deprived, recalling the chance he'd had and lost.

"As all of you know, our industry is suffering under constantly renewing threats." The speaker was from the home office in Cedar Rapids. Hair off the ears, white shirt, striped tie, unwavering gaze, his look mimicked an ad for retirement-plan advice, his words charged with purpose.

"Insurance plans of every sort—not just HMOs—are squeezing our bottom lines. Governments are pressuring us on pricing. Re-importation is no longer on the horizon—it's here. Our shareholders are scared, and rightly so. We need to change our expectations."

Lessing's commitment to success was waning. At least, success in his job, in drug sales. Shareholder value was crowding out self-achievement as the motivator, his motivator. The sense that a bigger, better Michael was inside him somewhere, hustling to get out, and that more achievement would bring gratification—that was dying in him. Now it was the shareholder who needed gratification. Well, the hell with that, he thought. He had a little rental income. If he could just find an agent for this new novel, someone serious, someone to believe in—and to believe in him—it would give his writing some traction toward a career.

His little beach town was growing more congested by the day, cheap money building in the gaps, pushing out the borders, big-box commerce digging in. Still, his town was okay and his life was okay. He had good friends, and his job had been good before this shareholder crap. Also, he didn't need to see the shrink anymore (even if his ex did!).

The sheer, ragged ridge of Punta Lobos angled down and out to the point, to a large rock that was split off the end. Two carrion birds rode swirling thermals, patrolling along the cactus-strewn cliff-edge. Gannets and shearwaters dived for fish or roosted among the hollows in the rockface where weather and the sea had carved their marks. The point got its name from the seals, los lobos marinos, wolves of the sea, that slept and fed on the east side, facing the Sea of Cortez. Good yellowtail ran in the current there.

In rivers, lakes, and the sea, on gear light and heavy, he'd hooked and fought thousands of fish, and they were all cousins. Big silver salmon on downriggers off Vancouver Island ran and bulled you like the yellowfin schoolies out of Cabo San Lucas. Pound for pound, the salmon weren't as tough, but they still bulled you like the tuna. Christmas Island bonefish were spooky, like brown trout cruising the weed beds in a clear Tasmanian lake. Hard to fool, both challenged your vision, your casting, and your patience. And when they ran, it was for the horizon. Sierra mackerel hit and ran like Zambian tiger fish, pipey and short-winded, but were easier to hook up.

He'd gone to Africa last year knowing tigers were the toughest fish to hook. Though he'd been wary, on the first day, with his own fly and his first good cast, he'd got a strike and hooked up, but then broke it off with a spell of buck fever. He didn't actually boat a fish until his last day. For the three days in between, every hit was a brilliant, megawatt shock, and he hadn't been able to set the hook in the fishes' marble-like jaws. The thick end of five grand, four days of travel into the Upper Zambezi, through a war-blighted East Africa, where the tension in the cities sandpapered your fears so raw you couldn't write until the living African night took over from the dreary, hunkered days—and he'd landed one fish. How had he felt?

He'd felt like he felt now. It boiled down to failure. Failure to be ready. Failure to expect the unexpected, so, when the big fish hits, your trace is too light, your hook too dull, your concentration weak. You strike too quick, too late, too soft, too hard. You fail. It doesn't matter how far you fly or drive or hike, what you see or eat or talk about with others. When you miss a fish, you fail.

Returning from Punta Lobos that afternoon, with a wind chop building in the channel, Lessing had two small yellowtail in the box, sore reminders of the twenty-pounder he'd lost in the morning. Up ahead, inside the point and a hundred yards from shore, a fisherman in another panga was onto a good fish, his rod arced in a C, his line stretched over the water like the finest spider strand.

Slowing a bit, Joaquín called to the other panguero, and Michael watched as they passed the time of day. Then Joaquín looked away, across at Loreto, a half-smile crimping his face into leathery corrugations.

"Jurel," he said. "Muy grande." A big yellowtail on the line.

Lessing held his gaze on his panguero's face. Then, at a noisy eruption from the other boat, he looked over. The bend was gone from the rod and the line was slack. The boatman was leaning against the gunwale laughing, and his angler was laughing as well.

He must be drunk, Lessing thought. He'd lost a big fish, and all he could do was laugh about it?

Back at the marina, Joaquín asked Lessing if he wanted to fish tomorrow. No, he said, he wouldn't enjoy another day like today, another day of disappointment.

That evening, Lessing walked to Casa de Mariscos for dinner. From the mouth of an alley, a ringing guitar backed up an accordion's song, and he crossed the broken paving stones toward an abandoned building where, graffitied in blue on a pink stucco wall, it said: ¡Cambié sus expectativas—por si mismo! Change your expectations—for yourself! He read the message and walked on.

He sat alone at Mariscos, at a small table near the end of the bar. He ate a meal of pezole, shrimp and beer, and thought about the old man at the tackle shop back home, about the blue-on-pink-stucco commandment, and about the years lost and those yet to come. After dinner, he found Joaquín in the square and told him yes, he would fish with him again in the morning.

Author’s Note: My first published short story, reflects some of the psychological and emotional factors at play in the minds of serious anglers, fresh-water or salt-.

*Originally published in City Works by City Works Press in 2007; 2nd Place in Sheridan Anderson Short Fiction Prize 2018, Fly-fishing & Tying Journal;

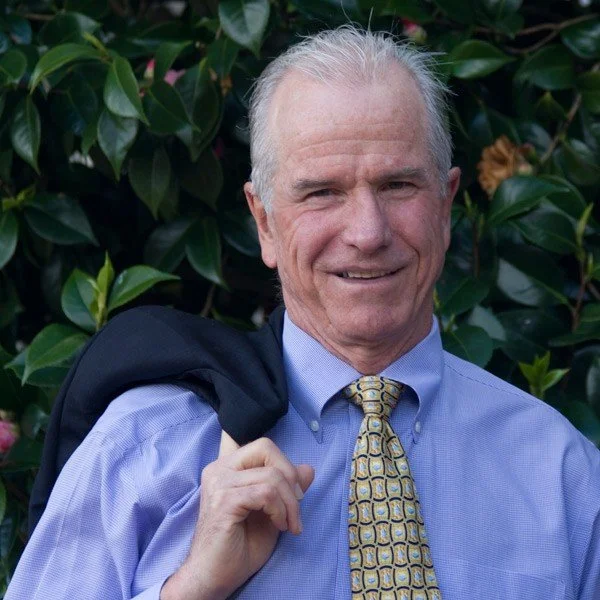

BIO: Lance Mason's writing reflects both his farm-town origins and his extensive travel abroad. He has explored, lived, and worked overseas for decades, traveling the world by foot, bicycle, motorcycle, train, tramp steamer, and dugout canoe, about 15 years of which was spent living in current or former Commonwealth countries. These experiences that have both enhanced and interfered with Mason’s writing life. His work has appeared in 50+ journals, collections, anthologies, etc., was included in Fish Publishing's 2025 Memoir Prize (Ireland), received a Silver and 2 Golds in the 2024 and ’25 Solas Awards, and his fiction recently appeared in ShortStoryStack (Palisatrium), Eerie River's BLADES, and Cowboy Jamboree's PRINE PRIMED.